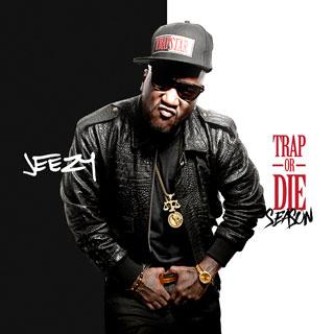

But once you delete the last half from your iTunes, you've got an EP-length release of ride-out music as fiery and visceral as anything you're likely to hear this year.Jay Wayne Jenkins (born September 28, 1977), known by his stage name Jeezy (formerly Young Jeezy), is an American rapper. By the time the tape ends, you're exhausted. "Ride Wit Me" somehow manages not to turn its Scarface and Trick Daddy guest-spots into gold. "Hood Politics" and "Go Hard" and "My Tool" reiterate the same motivational medication talk that Jeezy's done hundreds of times before, usually better.

After that, Jeezy starts to relent, cranking out decent but unmemorable tracks that just seem to take up space. Like a lot of mixtapes, Trap or Die II is too long, but unlike most, it's too long in a neat and orderly way, with almost all the strongest tracks front-loaded into the tape's first half. Jeezy and guest Plies come almost completely unhinged, screaming hoarse self-aggrandizement over what sounds like a symphony composed for car-alarms.īut Jeezy doesn't keep that energy up for long. The latter is, incredibly enough, Jeezy's new single- a bold move, considering that the thing can make you feel like you've got voices in your head screaming at you. It might be no accident that the two strongest songs here are called "Insane" and "Lose My Mind". It's severe, physical music, almost a circa-2010 Southern gothic take on the Bomb Squad's dizzying barrage. Drum patterns frantically jackhammer each other, trebley synth figures erupt out nowhere, and even the tracks that sample old-school soul seem to be almost entirely horn-stab. And guess what? It still sounds pretty great.įor the first 10 or so tracks of Trap or Die II, Jeezy's in rare form, finding tracks denser and more feverish than anything he's ever rapped over. But now he's back with the sequel to the mixtape that first put him on the radar, talking that same old drug-talk once again. Among other things, that was a smart way out of the endless drug-talk that his previous records had threatened to turn into cliche. On his last album, 2008's The Recession, Jeezy found a loose unifying concept that channeled all his strengths into something better, turning him into a voice for the anxiety about the then-nosediving markets. That lends him an urgency he must really have some shit to say if he's willing to scream over that insanity.

Jeezy likes his tracks to be huge, oppressive things, their heavy gothic melodies only underscoring the titanic chaos of the drums. But he also has arguably the best ear for beats of any of his contemporaries, which turns his handicap into an asset more often than anyone could've imagined. Young Jeezy might have the most limited delivery of any A-list rapper, an aging-attack-dog wheeze that he uses to bulldoze through tracks, hardly ever varying cadence or intensity.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)